This page is a work in progress. Please don’t critique too harshly as we work to get it just right.

Research 101

So, how do you learn how to research? In order to answer that question we need to take a closer look at the research process. Research is messy. To an outside observer, research may even look a bit like chaos theory. Even so, a good researcher is fully aware of the research process and knows exactly what is going on and why.

The Research Process

One of our favorite definitions of research was made by John Creswell from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln:

Research is a process of steps used to collect and analyze information to increase our understanding of a topic or issue.

You see, research is just trying to better understand the world around us. It’s nothing to be afraid of. However, as every seasoned researcher knows, it helps to have a framework that can help guide you as you work your way toward a conclusion. For every question asked, there are a thousand ways to proceed. You need to be familiar with the steps of the research process so you can stay on track and really know when you have arrived at a solid conclusion.

What is the research process made of? Let’s go on a journey into the amorphous cloud of research to find out!

Inputs and Outputs

The “What’s” of Research

Before we can start our journey, however, we need a question. Questions are always the beginning of the research process. Conclusions are the end. Only after we have a question can we try to find an answer! All of the good stuff—the journey of discovery—is sandwiched in-between. So grab a question and let’s go!

The easiest things to grasp when talking about the research process are the tangible things—the things that we can see, touch, read and write. For example, the research process starts with a question. A question is something concrete that we want to know—something we can write down. As we complete any step (or phase) of the research process we are left with one or more of these tangibles, which we call research outputs.

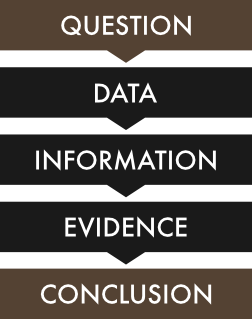

In research, everything is connected. One thing flows into another. As figure 1 shows, outputs from one phase are used as the inputs for the next phase. In other words, inputs are dependent upon the outputs of previous phases of the research process.

So what are these outputs and inputs? Between the question and conclusion, the three other parts form the skeletal scaffolding of the research process:

- Data

Data is raw, uninterpreted stuff. Given a field of research, data is the source from which researchers in that field gather information.

Data could include measurements made during experiments for a physicist or historical documents for a genealogist or historian. Data can even include research papers that are studied during the course of research.

- Information

Information is interpreted data—interpreted as knowledge of the research domain. Information should be understood by someone that is familiar with the research domain.

- Evidence

Evidence is interpreted information—interpreted in the context of the question. Evidence shows how the information answers the research question.

While these inputs and outputs seem very simple at first glance, the actual research process does not usually follow a predetermined path. Gathering and analyzing data often lead us into seemingly random paths as we try to build a conclusion. Yet at the end, we should be able to look back and see where the evidence comes from.

- Figure 1

- Inputs and outputs of the research process

Phases

The “How’s” of Research

Now that you know about the inputs and outputs of research, how do we move from one step to the next? There is a transition between each step of the research process where we take a research output and use it as an input for the next step, applying it in a new way. Each of these transitions between an output and an input is called a phase of the research process.

While we tend to lump all these phases together and call it “research,” each of these four phases has a very specific purpose and approach:

- Orientation

- During this phase the question “sinks in” and becomes structured for the researcher.1 The situation is assessed and the researcher becomes oriented to the possibilities.

- Exploration

- During this phase the researcher tries out some of the possibilities to see where they will lead. A good explorer will keep an open mind to make sure nothing is missed before proceeding.

- Investigation

- This is the stage to pursue the most promising possibilities further. Deeper digging is required to choose the best possibility.

- Proof

- During this final stage we can confirm or prove that the choice is right. Tests are performed to make sure that the conclusion fits with everything else that is known.

Of course, research does not normally progress linearly through these stages from orientation down to proof. It is an iterative process. Often, research follows a seemingly random and cyclical pattern. However, progress through these phases can sometimes happen so fast that we don’t realize it. Other times it takes longer. It depends on the problem at hand. This process continues until answers are found and questions are laid to rest.

If a mistake is made in an early phase, everything built later upon those outputs will be based on wrong assumptions. Remember the old quip: “garbage in, garbage out.”

Outputs form the future possibilities that pull us onward through the maze of research. As we work toward a conclusion, we select some outputs to use as inputs for the next phase and continue until we can finally answer the question. Often, when we start arranging evidence we hit a dead end or find that we don’t have enough to build a solid conclusion. Then it becomes necessary to revisit earlier phases and do more digging. However, as figure 2 shows, with each phase and iteration, the conclusion becomes a little more sure.

- Figure 2

- Phases of the research process. As you progress through each phase, the conclusion becomes a little more sure.

A Research Framework

These phases, together with the inputs and outputs, form a conceptual framework that helps us to know where we are in the research process, kind of like a GPS device helps us know where we are while navigating through unfamiliar territory.

“Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?”

“That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,” said the Cat.

“I don’t much care where—” said Alice.

“Then it doesn’t matter which way you go,” said the Cat.

“—so long as I get SOMEWHERE,” Alice added as an explanation.

“Oh, you’re sure to do that,” said the Cat, “if you only walk long enough.”

Research is a lot like chess. Strategy is required to assemble the bits of evidence the right way. However, one difference is that chess has a very finite number of possibilities, while research is more dynamic with almost limitless possibilities. With research, you discover the rules and the playing pieces as you go along. But, like chess, your eventual placement in the game is the sum of all the previous moves you have made on the game board.

We, as researchers, ultimately choose the course to follow. Choice is the fundamental navigator of the research process. Choose carefully.

A Unit of Research

So this framework idea sounds nice, but how do we keep track of it all? Large research problems can be overwhelming. If we break up these large problems into bite-sized pieces, research becomes more straightforward. Like scientists that break matter down into atoms, we need to isolate a unit of research so that research can be more manageable.

No doubt about it, research is hard. But too much time and effort can be spent in bookkeeping, and not in putting the pieces together. If we can reduce the time spent on bookkeeping, we will have more time to think about how to put the pieces together.

We have taken apart the research process to figure out how to make the process easier for researchers. What we found is that while computers are not very good at doing research, they are really good at organizing research. Computers can take care of the bookkeeping so that researchers have more time to put the pieces together.

- Figure 3

- Just like an elephant, research can be broken down into small, manageable, bite-sized pieces.

The Research Case

So how can we break up research into smaller pieces? The answer is obvious—in our minds we already group little bundles of research together almost instinctively. In fact, we’ve discussed it already! There is a natural demarcation between these little bundles of research, bounded by a question and a conclusion. We call these little bundles research cases.

Research cases are the building blocks of research. They’re also the foundation of what we are trying to do as a company.

A Multiplicity of Research Cases

Once a research case has been built, other research cases can be built on top of it. Research cases can be grouped into projects. Research cases can be shared with others, allowing others to see not only the conclusions, but the entire research process including the evidence, information, and data the conclusion is based upon.

As we dig deeper into a research problem, one question often leads to more questions.

The outcome of any serious research can only be to make two questions grow where only one grew before.

- Figure 4

- Research cases can be built on top of each other. Often, a conclusion of one case can be used as evidence in another. Thus, a graph (or multiplicity) of research cases emerges as research progresses.

Case Etymology

There are many ways the word case is used, from legal proceedings to enterprise resource planning systems. Researchers talk about “building a case.” A branch of research, called case study research, has even been built around this idea. Case study research is common in social, educational, and political research. Dr. Gary Thomas of the University of Birmingham has described case studies as follows:

Case studies are analyses of persons, events, decisions, periods, projects, policies, institutions, or other systems that are studied holistically by one or more methods.

While our notion of a research case derives from many of these wonderful ideas, our definition specifically refers to a software structure that could be thought of as a bundle or chunk of research, and has applicability in many diverse domains.

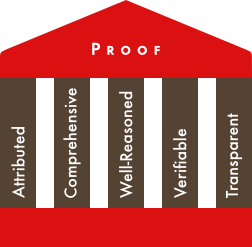

The Five Pillars of Proof

So after we have done some research, how do we know how good it is? Just as we need to break down a large research problem into research cases, we need to be able to look backwards and evaluate our research. An inward perspective is needed for this. We can know how well our research “measures up” by looking back and comparing what we have done to a standard. The standard varies depending on the domain, but generally includes the following checkpoints:

- Attributed

- Don’t be a weasel. Give credit where credit is due.

- Comprehensive

- Research should be thorough. Did I cover all my bases?

- Well-Reasoned

- Think about it. Does the conclusion make sense logically?

- Verifiable

- Can someone else retrace my steps? Will they end up at the same place I did?

- Transparent

- Don’t hide your light under a bushel. Explain what you mean so that someone else can understand it.

Luckily, research cases come in handy here as well. If each research case in our project measures up, we know that the whole project measures up too.

We need to periodically look back and evaluate our progress, making sure that we have not strayed from the path and that we have not left any stone unturned. Peer review gives us a second opinion as others look back on our research to assess its quality.

All research conclusions involve opinion. It is up to you, as a researcher, to prove that your opinion is right.

- Figure 5

- How can you prove that your conclusions are right? The strength of your proof can be measured with the help of five checkpoints.

End Notes

Adrianus Dingeman de Groot, Thought and Choice in Chess. (Amsterdam Academic Archive: Amsterdam University Press, 2008), 103. We learned much about the thought processes involved in research by applying ideas from his experiments with chess. ↩

Additional Resources

- Research on Wikipedia

- Case Studies on Wikipedia

- Working with Historical Evidence: Genealogical Principles and Standards: an excellent explanation of genealogical research by Elizabeth Shown Mills

- Argumentation in Artificial Intelligence