Putting the Pieces Together: Technology

This post started as a follow-on to a post I am writing about the culture of the Scholarly Commons in response to the Scholarly Commons San Diego workshop held last September by FORCE11. But, as it sometimes turns out in this funny thing we call life, it is time to release this post, and I am still working on the one about culture. Don’t worry—this post is not about specific technologies, but about what needs to be enabled by technology to allow for what I’m calling, for purposes of this discussion, scholarly commoning.

As this is my own response to the San Diego workshop and to our discovery process so far relating to the Scholarly Commons, it represents my own views only, and not necessarily the views of those in FORCE11’s Scholarly Commons Working Group or even its steering committee. Each of us involved in this project are coming at this from different perspectives, so it is no surprise that we are not always in complete agreement about what we would like the Scholarly Commons to be. We are each a product of our own experiences and backgrounds, and each of our backgrounds is quite dissimilar. Even though this makes things difficult sometimes, I view this as a good thing in general, because it has brought more perspectives to the table and has forced us to look at what we’re doing from many different angles.

Ever since we started this thing, a central premise has been that we would ‘re-imagine scholarly communication starting from scratch as a system explicitly designed for machine-based access and networked scholarship, and not simply adapted from the paper-based system.’1 Throughout the course of us working on this, however, it has become evident that ‘from scratch’ and ‘networked scholarship’ mean different things to different people. For some on this steering committee (and likely others), these terms convey more of an idea of an incremental realignment of existing platforms and services, some of which have been studied in the 101 Scholarly Innovations project. But there are also those, myself included, that have been thinking of these terms on a more foundational level, of open approaches and emerging technologies that could actually change the conversation, such as distributed affordances, HATEOAS, and machine-based ontologies that could help connect researchers and research across tools and platforms, providing new interactions for scholarship that would open up the research process and give us the ability to do things that we have never been able to do before. In trying to reconcile these two approaches, I have wondered whether it is possible that the idea of the Scholarly Commons could encompass both.

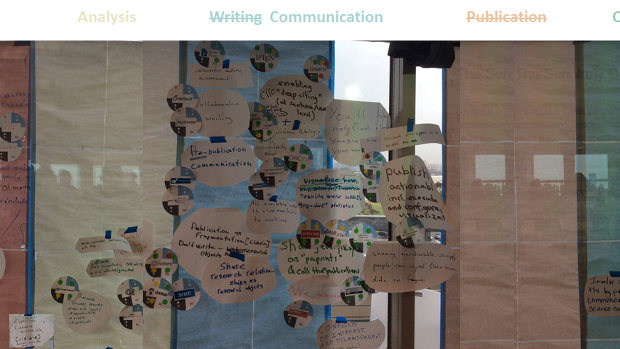

There is a general consensus among us, I am pretty sure, that the Scholarly Commons is scholarly communication in a modern setting, one in which we are not constrained by the limitations of print publishing. But the definition of the Scholarly Commons goes much deeper than that, and, as they say, the devil is in the details. The Scholarly Commons represents scholarship reinvented for our modern era, and whichever the approach to do that, I am hoping we’ll take the best of the past, the aspirations and thirst for understanding that have motivated mankind for thousands of years, and redesign the whole system from scratch to fit our current needs and desires, so that, hopefully, in the end, we will have built, using the best of modern technologies, ‘a constellation of working alternatives driven by a different logic.’2 As this essay is, in part, a review of the San Diego workshop, I want to structure my thoughts at first around the main track of this workshop, which was devoted to ‘putting the pieces together’ by comparing the community vision of the Scholarly Commons against our current state of chaotic innovation.3 While there were several unworkshop sessions, the main track was designed to lead participants through an exercise of ‘compliance checking’ existing tools to see how well they conformed to the latest rendition of the principles of the Scholarly Commons. One of the topics that pops up every once in a while lately in the discussions in the Scholarly Commons working group is the concept of compliance. I think this comes from a natural desire to understand what the Scholarly Commons is—to wrap our brains around the idea, and the hope that if we know where the boundaries of the Scholarly Commons lie, we might be able to reduce the Scholarly Commons to some transparent explanatory paragraph or set of principles. Following that type of thinking then, the question of whether or not something belongs within the commons is based upon whether that thing complies with certain agreed-upon principles. But the word compliance, to me, conveys more of a heavy-handed, top-down sort of idea, and promotes exclusivity over inclusivity. I think that for us over the past year this argument has been more of a distraction that has held us back from discovering more what the Scholarly Commons is all about. From my viewpoint, the Scholarly Commons is more about enabling interactions and the contributions that result from those interactions. In what we’re trying to do, there is this idea about lowering barriers and reducing friction. The things we’re working with either fit together or they don’t. A better word for this type of interactivity might be compatibility, which, in a telecommunications context, means ‘the capability of two or more items or components of equipment or material to exist or function in the same system or environment without mutual interference.’4 We use and build upon resources that are compatible with our manner of working. If there are resources that don’t fit, there is no place to put them. They don’t help but interfere with progress, so we just don’t use them. Compatibility puts the focus on fitness for use rather than on obedience, compliance, or even social expectation. So as far as I could tell, the hope for this main track was that we would discover a new system by looking at and reacting to elements of the old system, and then filling in any gaps that we find. I struggled with this approach in the days leading up to the workshop. I had little hope that we would discover some preexisting solution at this workshop that has just been waiting for us out there by looking at all the components of the current system. Cultural change and innovation don’t happen that way. Besides that, many of the tools that are currently used for scholarship are based on cultural practices from which we are trying to get away. To create a new system, we need to take the current system apart, looking at the original motivations that created the pieces that we have, and then take those motivations and design a new form to fit our current context. But I wondered how well we would come up with something tenable for the future when we were structuring the discussion so tightly around the current system. We were not going deep enough. We need something incredibly basic, something new that does not yet exist (or has been lost)—a different logic around which a new system could be shaped. To explain what I’m looking for here, allow me to share a similar fallacy and resulting struggle in the practice of medicine: One essential characteristic of modern life is that we all depend on systems—on assemblages of people or technologies or both—and among our most profound difficulties is making them work. In medicine, for instance, if I want my patients to receive the best care possible, not only must I do a good job but a whole collection of diverse components have to somehow mesh together effectively. Health care is like a car that way, points out Donald Berwick, president of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement in Boston and one of our deepest thinkers about systems in medicine. In both cases, having great components is not enough. We’re obsessed in medicine with having great components—the best drugs, the best devices, the best specialists—but pay little attention to how to make them fit together well. Berwick notes how wrongheaded this approach is. “Anyone who understands systems will know immediately that optimizing parts is not a good route to system excellence,” he says. He gives the example of a famous thought experiment of trying to build the world’s greatest car by assembling the world’s greatest car parts. We connect the engine of a Ferrari, the brakes of a Porsche, the suspension of a BMW, the body of a Volvo. “What we get, of course, is nothing close to a great car; we get a pile of very expensive junk.” Research or scholarship, just like medicine, is not simply a matter of lining up tools into a usable workflow. We need to approach this problem in a systemic way, considering the many and various aspects of this new system, including production, governance, culture, economics, and technology. The Scholarly Commons will look different than our current system, and to enable this different system, we need something fundamentally different that will drive this different culture. Putting those concerns aside for a moment, the compliance exercise was very enlightening for me in some unexpected ways. I need to add here that, while this was the main track of the workshop, there were other discussions going on, and I spent most of the day bobbing between the discussions going on, observing and trying to understand the participants’ various perspectives, so my understanding of some of the discussions may be incomplete. As for the exercise, after the tools went through the ‘compliance checking’ activity, they were plotted on a graph and grouped by research phases based on the current publication paradigm. Participants were invited at that point to describe the path that they would take (if there was one) through these tools in the course of work in their particular domain of study. The participants drew their path onto a transparency that was overlaid on top of the tools. These transparencies were then grouped by domain… …and then superimposed on top of each other so that common patterns could be seen. Here are some examples: As you can see, while there is some overlap, the paths, even within domains, are very idiosyncratic. People are particular about which tools they want to use, and often there is more than one path to take—more than one tool that can be used to get a job done. Certain tools might even be used to gain a competitive advantage. Here are a few of the group’s thoughts that emerged during the compliance exercise: As for my first bit of enlightenment, it was good to talk about current practices. So much of my time I spend thinking if we could start over from scratch, what would the world look like? and I don’t spend as much time thinking about the difficulties that others are facing of transitioning to this new world from the current system. For example, one participant was threatened with dismissal from her doctoral program if she chose to publish a paper open access. And that’s just the resistance placed against the Open Access movement, which has been going on for many years now. Compared with the Open Access movement, the Scholarly Commons seems like it is from another millennium, or at least another century. As much as it sounds nice, and as happy as it would be to work in this new world, the transition to new ways of working together is not going to happen overnight. It is not enough to know what our destination is—we also need to know how to get there from where we are now. Of course we can’t expect to figure all of this out in one workshop. But we must address the right questions. And we need to have the right goal. Merging the results of this exercise with some of my earlier thoughts in this essay, it may be that the commoning—the practices, not the tools—is what needs to be compliant. Here it is important to understand that, besides the logical fallacy that I described in the first section, this exercise was trying to illuminate what is common among tool use in the current paradigm, not necessarily what would be required in a commoning paradigm. The exercise was designed to find common patterns, not patterns of commoning. While this was useful in some ways, it leaves more important questions unanswered, such as is there a shared resource of a scholarly commons? If so, what is it? and who is the community that cares about or manages that shared resource? If we don’t have answers to these more fundamental questions, then we really have no way to know whether any of the answers we come up with are right or even what any of the other questions are. Common and commoning are not the same thing, and a common practice does not a commons make. Yes, some existing tools align with practices that we would likely want to carryover into this new way of working, but looking back, I think the focus of this exercise was too shallow. If we had kept the discussion more abstract and focused on specific practices rather than on specific tools, we may not have had the eventual disintegration of the main workshop track as so many of the participants left to join other excellent discussions. Most of the tools we were studying in this exercise were designed for the research culture and technical infrastructures of the Global North and just did not connect with many of the people that we brought from around the world. But perhaps even a focus on specific practices would have been too shallow as well, and we should have taken a step back and discussed something else, such as the need for and approaches to global peer-production. Even so, I did not expect the participants to react this way, and I think this was an important negative result to obtain and from which we should learn. Our process as so far in defining the Scholarly Commons, aside from the few workshops that we have held, has been mostly limited to seeking feedback when we were nearing a finished product. Our design process has not been very open, not because we we haven’t wanted it that way, but because of the lack of tooling that preserves the continuity of a broad-reaching, multi-faceted exploratory research process. I believe that the future really is a happy place and we need ways to do this better! Throughout this exploration (and it has been a luxury to be able to explore this topic so intensely for so long), while I have learned much from the many perspectives that have been shared, I have found it particularly interesting that we have not yet discussed together the definition of scholarship. I think we’ve focused too much on trying to create something appealing to the current professional community of scholars, scientists, and researchers. We are trying to create a new system, but if we try to design this system primarily motivated by a desire to please the current players, we’re going to give them something that looks a lot like the system they currently have, and not the system that we desperately need. Revisiting our definitions of scholarship, science, and research, I feel, is a necessary part of defining the Scholarly Commons. If we go back far enough, say three or four hundred years ago, scholarly communication didn’t happen in the sort of static, dissemination-oriented way that it does now. People wrote letters to each other, sharing their progress in understanding openly, including hunches, questions, impressions, tentative conclusions—the whole gamut. It was a collective effort to gain a greater understanding of the world, one which was empirical and not based on dogma. It united people across languages, cultures, nationalities, and backgrounds. It was only later that, for motivations which I think were at odds to the original intent and mostly based on the economical limitations of print, these letters were editorialized, and the scholarly article was born. Eventually researchers submitted articles to the journals directly, and started using publication to establish scientific priority. You may think that this was a natural evolution, but I think we lost something in the transition to more ‘modern’ scholarly communication. I am reminded of a quote that I’ve shared before: While publication and distribution of the Philosophical Transactions certainly contributed to the diffusion of knowledge, it did not provide for the flexibility, openness, manoeuvrability and relative rapidity of interaction that correspondence did. In short, the Society’s correspondence encouraged a more participatory science. I would argue that what we have lost we need to revive and reintroduce into our concept and culture of scholarship, and that this idea of ‘flexibility, openness, manoeuvrability, and relative rapidity of interaction’ is intrinsic in the idea of the Scholarly Commons. We can’t really invite participation and collaboration in this way unless we open up and expose the research process at this level of granularity. We need to be publishing at the granularity that would allow us to actually work together throughout any part of the research process. Otherwise we’re still working in silos, albeit smaller, distributed ones. We need the spirit of scholarship and enlightenment that existed in the Republic of Letters, and it comes quite naturally if we can stop taking ourselves so seriously. In order to create a truly open, collaborative, egalitarian culture of scholarship, we also need what was in the researcher’s mind in the first place, as the knowledge was designed. We can’t continue publishing or disseminating only closed forms. We need new forms that invite participation. We need to publish the research, exposing it more at the cellular level (or tesseral level, if you will 😊). In order to create this new culture, we need more than open notebook science, research protocols, reproducibility, or even static depictions of researcher workflows. All of these things are great, but they don’t invite participation by themselves. We’ve talked a lot about attribution, but there’s something more to the concept of the researcher that we’re not yet talking about that much. We need something social and dynamic that brings together the pieces of research and draws people into the process (while, of course, preserving the attribution, integrity, and openness of the contributions). If we can find effective ways to communicate more openly throughout the process, many of the existing forms of scholarly communications will either change or go away. The Scholarly Commons should be a jumping-off point to new ways of working together, taking the best ideas of how to do scholarship in a modern setting, setting aside as many of the undesirable social, cultural, and technical limitations as possible. As I was sitting there in the workshop, thinking about all the above, the answer came to me slowly but clearly. A thought occurred that had somewhat to do with the exercise, but more indirectly: because the research processes were made explicit and studied this way, it allowed us to reason about, find patterns, and learn from them. Then a flood of questions entered my mind: What if we could look at the research process in more of an explicit, tangible way? Isn’t it the process that needs to be open and replicable? So why are we not publishing the research process, even across tools, as the fundamental scholarly output? If research or even knowledge discovery happens sequentially for a researcher, why are we not publishing the journey of the researcher? If the process was the product, many of the problems we are facing right now in scholarly communications relating to reproducibility, participation, and the integration of scholarship into society would be greatly diminished or eliminated completely. Researchers would also have something to show for all their thinking. From this perspective, the entire research process could be viewed as a sequence of decisions. The researcher’s thoughts and and the process of how they arrived at conclusions should form the basis of research publication and collaboration. I’m not advocating here that we capture a complete record of everything that a researcher is doing. But we need make explicit this common thread—this sequence of decisions—that drives the research forward, and researchers should have the flexibility to choose deliberately, at each point of decision, whether or not to make a thing part of that thread. This thread needs to be an integral part of the research experience, something that researchers curate as they go along. If we keep this part implicit, or leave it to ex post facto analysis alone to attempt to reveal it, we end up not very far from where we are now: publishing about the research, instead of publishing research, and our ability to effectively collaborate deeper into the research process will be impeded. An article about computational science in a scientific publication is not the scholarship itself, it is merely advertising of the scholarship. The actual scholarship is the complete software development environment, and the complete set of instructions which generated the figures. But where do we draw the line between implicit and explicit? Is it enough to know which tools the researcher used and when? The tools are part of it, but stopping there would give us a very limited perspective into the research process. We need to ask ourselves, what is our goal? and then what is of value in reaching that goal? If our goal is to create a new culture of scholarship, what would change the culture? What about the questions and intentions of the researcher? Sharing openly at this level may be just enough to change the culture, as it would invite people into the process and place the emphasis on potential participation rather than on prior prestige. To give an example of what I mean, allow me to share my experience designing the logo for the Scholarly Commons. As I went along, I made a conscious effort to explain each step, impression, question, and resulting decision of the design process. This is the spirit and culture of the commons! Done this way, the process is open, transparent, and invites participation. It is easy for anyone to ask, ‘Did you think about this or that?’ and contribute in context. It is easy for anyone to get involved in the design process, wherever and whenever the feel they have something to contribute. Obviously, doing this with a Google Doc is less than ideal, but I hope you can see what I am trying to show. To summarize, in my view we need technology to help us with two things that are actually very complementary: we need a way to expose and preserve our own individual journeys of discovery, and guides to help us through the process. As much as we’ve focused on principles and culture (and they are certainly the driving force in this effort!), we need an enabling infrastructure for commoning. We need to make the scholarly and scientific process easier, and then enlarge the doors and allow others to come and participate in this great endeavor! When it comes down to it, making the transition to this new culture is, in large part, a user experience problem. The existing lack of interoperability between tools is actually an opportunity for something better. Going back to Everett Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations, we need an advantage over the current system. If we can create a better research experience, one that is open and invites anyone that desires to come and play and bring what they have to offer, then we have created an advantage. We will then have the potential and power to transform the culture. We also need the ability to try out this new system without worry of losing what we already have. Rogers refers to this as trialability. The Scholarly Commons is something that enhances—it does not detract or take away from the current system, but is an alternative that can exist alongside existing systems! If you are publishing your process openly, there is nothing to stop you (or someone else, for that matter) from writing up a summary for a journal, whether open or proprietary. Either way, the underlying research is still open for anyone to learn from or build upon. The Scholarly Commons is not anti anything, but invites all to come and participate, which will enable it, potentially, to scale bigger in scope and influence than existing systems are capable. Because it will be a fully functioning alternative driven by a different logic, the Scholarly Commons will eventually have the ability to displace existing systems. In fact, the description of the original idea behind the first workshop reads: The first workshop would take up a 1K challenge idea by Dr. Sarah Callahan from FORCE2015: What would research communication look like after a clean start? A common theme that emerges from FORCE meetings in that many of our ideas for reforming scholarly communications spring from 350 years of tradition around scientific dissemination. As shown by the discussion on credit systems at FORCE2015, we don’t question the basic assumptions behind our current systems which are often electronic implementations of old practices that pre-date machine-based access to information. This workshop will re-imagine scholarly communication starting from scratch as a system explicitly designed for machine-based access and networked scholarship, and not simply adapted from the paper-based system. For example, what would scientific discourse look like if we didn’t have a 350 year old tradition of describing data rather than publishing it? What if the Ingelfinger rule stating that all articles must present new research had never been adopted? If the impact factor built around coarse citation systems hadn’t taken hold? If science had always involved the work of large teams? Bollier, David. Commoning as a Transformative Social Paradigm, Nov. 2015, p. 9.↩ The description of the original idea behind the second workshop reads: The second workshop will be devoted to Putting the pieces together by comparing the community vision against our current state of “chaotic innovation”. How close are we to realizing this vision? What pieces do we have? Where are we lacking infrastructure, expertise, tools, principles, or incentives? Where does current scholarship need radical retooling? What opportunities exist for the community to fill these gaps, and how can we create community buy-in around proposed solutions? From Wiktionary.↩On gaps and systems

The exercise

Scholarly Commoning

The process is the product

A relative advantage