Opening Knowledge

All that we do in this company is motivated by our mission, which is, ‘to open up the knowledge of the world, so that light and understanding will be more accessible to everyone.

’

We live in the information age. Why does knowledge need to be opened up?

Knowledge is trapped right now in books, on the Web, and in people’s heads. If our goal is to make light and understanding more accessible to everyone, we need more than access to books, libraries and other repositories of knowledge. We need to lower or remove barriers to the transfer of knowledge from one person to another. Transferring knowledge is harder than it needs to be, often requiring a lot of explanatory background information because the connections in logic of a particular nugget of knowledge are not linear. Research, at its essence, is simply structured learning, and is the process of connecting pieces of information together to create a new nugget of knowledge. We need easier ways to share these nuggets of knowledge. We also need to be able to share knowledge in more open, personal ways. Knowledge needs to be accessible in whatever way people think.

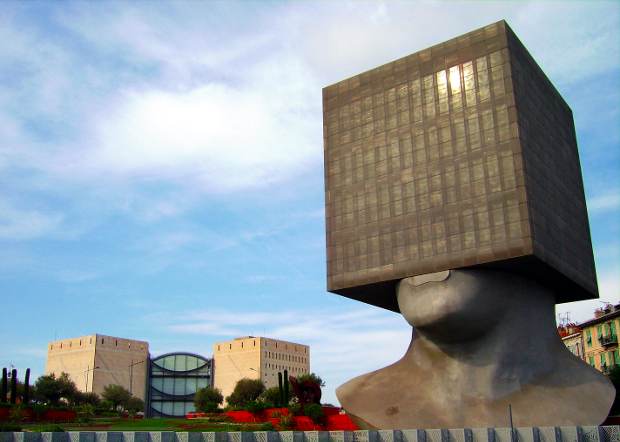

A library in France is a good metaphor for how knowledge is trapped and inaccessible right now. If you look at the picture below, you notice that this library, officially named La Tête au Carré (The Square Head), looks like a well-formed classical bust, up to the bottom lip. The rest is obscured by the opaque aluminum block that is the top four stories of the library. Nobody can see into the library from the outside, but because it is covered with finely perforated aluminum mesh, the people inside can see out. It’s hard to tell whether the library is depicting someone male or female, old or young, happy or sad. Neither can you tell what is in his or her mind, nor what he or she is thinking.

Libraries are repositories of knowledge. You could think of books, the Web, and people as libraries. All of these things, especially each of us, are vast repositories of knowledge! I’m not sure whether the sculptor, Sacha Sosno, was trying to depict this, but to me, La Tête au Carré screams of the impenetrability of the human mind. Even if we’re able to discern all the visual features of the heads of the people around us, it is still hard to share understanding with each other. As much as it would be convenient, we can’t peer into each others minds, or send out packets of understanding to another. Our ability to communicate knowledge is limited. We walk around and interact with each other as if we know each other, yet so much of who we are is not revealed to the people around us. In some ways this is a good thing. We each get to choose what and how much to share of our private selves with others. Even so, every time we try to share our thoughts and discoveries with each other, we have to translate the constantly flowing ideas of our minds and hearts into the much more limited medium of language. When we are directly in the presence of others, we have other tools at our disposal, such as gestures, expressions, inflection, and dynamics, but over long distances we experience increasing barriers to communication, especially when all we have to work with is prose. Prose gives the impression that it is precise, but in practice leaves much open for interpretation. Ambiguity is easy to introduce, and can confuse not only people, but machines as well. And even if we were perfect at our communication skills, people only share what they want to share with others. Much of our knowledge and understanding remains on the shelves, so to speak. And our diminishing attention spans make the problem all the worse! Rather than being left to guess the meaning between the lines, as Sosno’s sculpture suggests, we need the ability to share what is in our heads more directly.

In the current scholarly ecosystem the situation is more bleak. The paper publication process is too slow and isolated, not having changed much from what it was 350 years ago. Commercial publishers put research articles behind paywalls, charging consumers $30–40 for access to each. And the original authors or researchers get none of the profits. Even with access to an article, very few of the underlying connections in logic are ever published, especially when page limits constrain how much a researcher can share in the first place. This makes it hard for others to reproduce or build upon the research results. Even further, research that doesn’t turn out as hoped is normally not published at all. While the researcher may remember the result, the world doesn’t. For all intents and purposes the research is obliterated, which leads to a lot of duplication of work and wasted efforts. Talk about a communications nightmare! In some ways, the way scholarly information used to be shared (in the Republic of Letters) is better than our current situation—at least the culture accommodated a more open and participative approach. In present scholarly communications, even in the best of circumstances, we’re only publishing a part of the picture, like Sosno’s sculpture above, leaving the rest up to the imagination.

Stepping back a bit, I think it’s interesting that the World Wide Web is a graph of nodes and edges, but we as humans extract knowledge from it primarily by reading documents. While the Web is a vast improvement over the printing press, we must constantly go through the process of translating prose into information, and then connecting those pieces of information into knowledge in a way that our minds can understand. And then to write a web page, we need to translate our knowledge into prose that someone else can later disassemble and assimilate in the same way. What would happen if we used the Web in a different way? If we sidestepped this translation process and dealt with knowledge on the Web directly?

Maybe my hope for the future has come from reading too much academic writing, which much of the time doesn’t deserve the distinction of prose. Most are not enjoyable to read, and don’t seem like they were very enjoyable to write in the first place. As I say this, please don’t misunderstand. I have read well-written papers, and I believe that, even in scholarly communications, there is a place for well-written prose! But situations exist that are not a good fit for the form. Prose can be added on top of the research like icing on a cake, but intricate prose should not be required in order to share the nuts and bolts of knowledge creation. The way papers are currently written, authors attempt to pull together elements from their experience in order to share something intelligible. Without fail, important elements end up getting left out or forgotten. And the writing process filters information that the author deems irrelevant to the problem at hand or tacitly understood by the intended audience. Beyond that, our systems of citations are rooted in a two-dimensional world, and have not been able grow beyond this limitation. Footnotes seem to be the best tool that we currently have to describe the connections between pieces of information, but are lousy at preserving the context and meaning of those connections. There are huge opportunities here to improve the quality of the research experience.

Scholarship is currently assumed to be the domain of the scholarly elite. In the future, we see research as part of the everyday life of many types of people, from many different backgrounds, contributing to the world’s knowledge in many different ways. You don’t need to be a PhD to contribute meaningfully to the progress of knowledge! Some people know the right questions to ask, and other people are better at finding answers. Everyone knows different things and can bring a unique perspective to a question. In general, we want to change how research is done and perceived. A new research culture is growing, and we want to help it grow. You could compare what we are trying to achieve to the beginnings of the World Wide Web. In the early 90’s, the Web was the domain of technical futurists. Now the Web is cool, and everyone seems to be on the Web in some form or fashion. Anyone can become a web developer, blogger, or contribute something in some way, without anyone else for permission. Anyone—a curious student to a professional scholar or a seasoned entrepreneur to an aspiring researcher in a third-world country—should be able to share their journey of discovery in a simple, open way. This mechanism should be simple enough to track elementary questions and answers, and powerful enough to handle complex, data-intensive research. It needs to open doors for collaboration within a research field and bridge fields of knowledge that have traditionally been isolated. We need something that allows anyone to publish every bit of the journey, from the most random piece of evidence to the most profound analysis in real time, as the research is progressing. And all this research needs to be accessible not only to people, but to machines as well.

So why does knowledge need to be opened up? And what would be the benefit of making light and understanding more accessible to everyone? We need a greater ability to understand each other, especially over great distances and across cultures. We need to take advantage of technology that can make it easier for us to understand and explain difficult concepts and relationships. We need to lower barriers to the sharing of knowledge so that light and understanding is more accessible to more people. What will the effects of this be? I don’t know, but I know it will be good. More people will see eye to eye and understand each other. More people will be able to be helped. Our understanding, individually and collectively, of the world around us, its past and future, will improve much faster than otherwise. What we’re aiming for here is more than an improvement of research communications—we’re talking about a whole new way to share knowledge!

And if we’re serious about sharing knowledge, we need to be willing to expose our minds to the world.